In the fast-paced, innovation-driven world of New York City, intellectual property (IP) can be your business’s most valuable asset. From startups in SoHo to tech firms in Midtown, safeguarding your ideas, designs, trademarks, and inventions is essential for long-term success. But with NYC’s fiercely competitive business landscape, navigating intellectual property law requires more than just good intentions—it demands legal strategy, knowledge of IP rights, and the guidance of a skilled intellectual property attorney in New York.

This comprehensive guide will walk you through everything you need to know about navigating intellectual property law in New York City, with practical steps, expert strategies, and key insights from top IP attorneys in New York.

What Is IP Law?

Intellectual property refers to intangible creations of the mind used in commerce and business. These creations can be protected by law to ensure that others cannot exploit them without permission. There are four primary categories of IP protection:

- Trademarks

- Copyrights

- Patents

- Trade secrets

Each category plays a unique role in safeguarding different aspects of your brand, product, service, or idea.

In a vibrant economic hub like NYC, home to tech disruptors, creative artists, software developers, fashion icons, and culinary entrepreneurs, your IP represents your unique competitive advantage.

Source: Forage

The Four Pillars of IP Law Protection

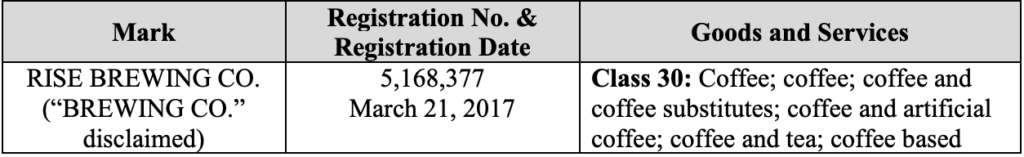

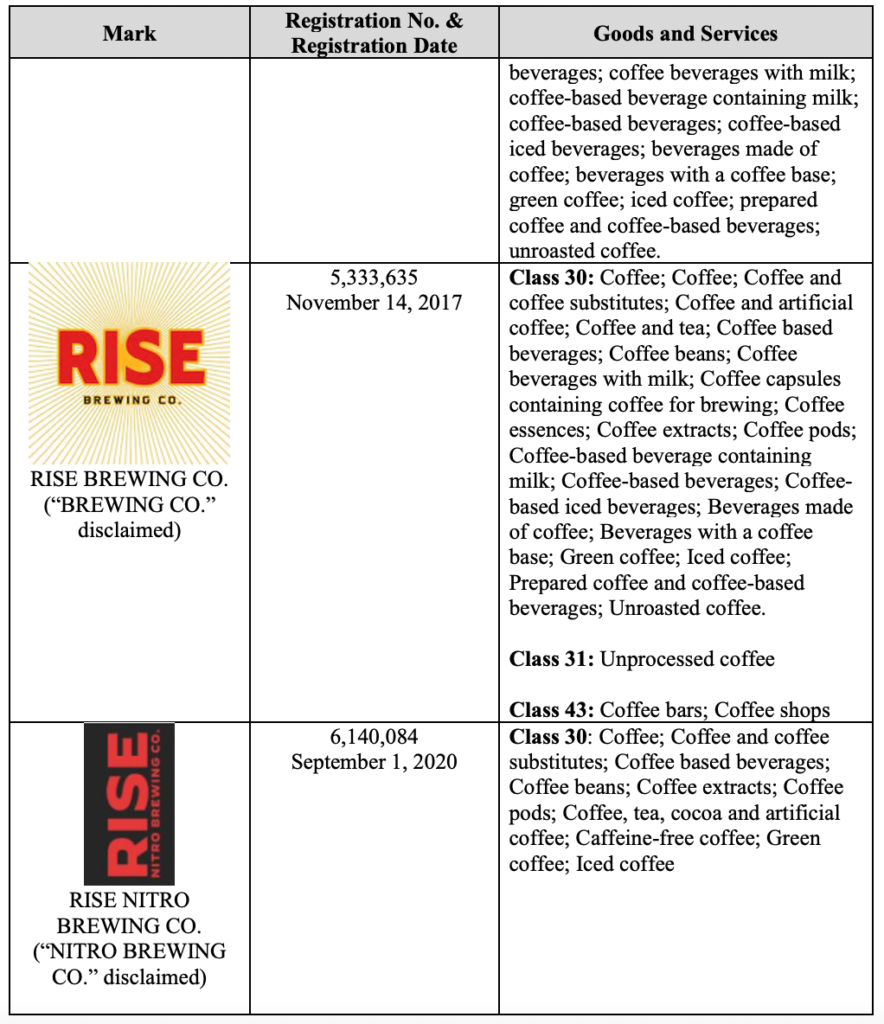

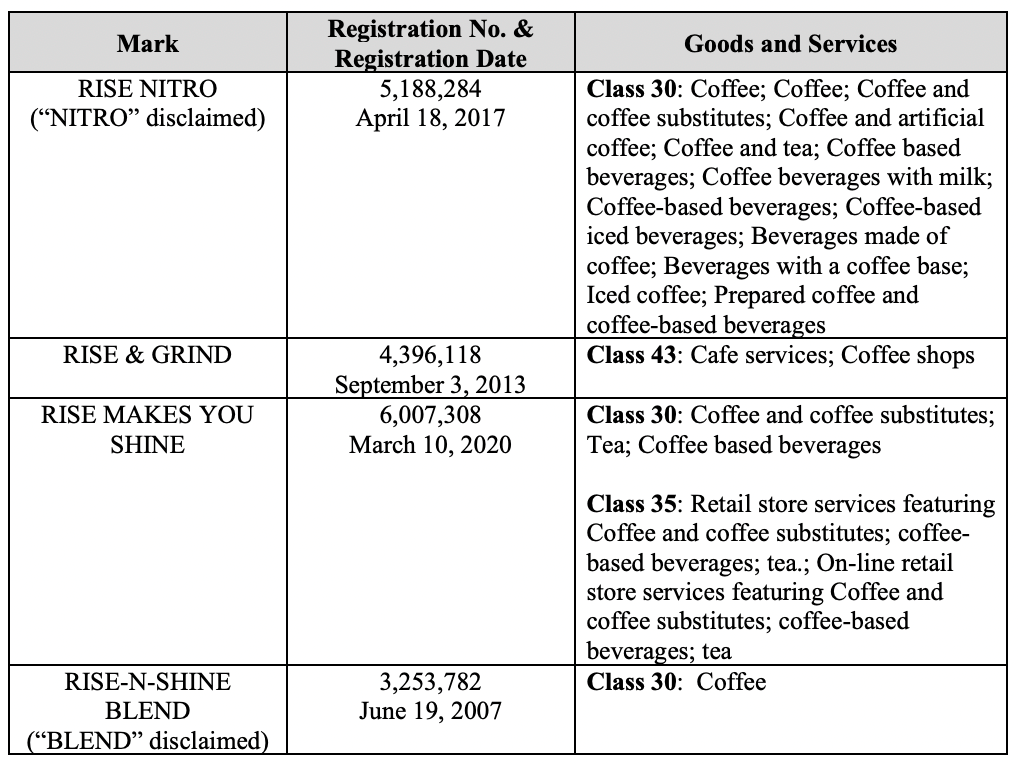

1. Trademarks

A trademark is any recognizable word, phrase, symbol, or design that protects brand names, logos, slogans, and symbols that distinguish your business from others. Think of logos like the Nike swoosh or slogans like McDonald’s “I’m lovin’ it.”

In New York City, where hundreds of new businesses emerge weekly, trademark protection is essential to avoid brand confusion and legal conflicts.

Key Steps to Trademark Protection:

- Conduct a Trademark Search: Use the USPTO database or work with a trademark attorney in New York to ensure your mark isn’t already taken.

- Register Your Trademark: File with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) for federal protection. Consider state-level registration as well.

- Enforce Your Trademark: Monitor for unauthorized use, and issue cease-and-desist letters or initiate legal proceedings when necessary.

2. Copyrights

If your business produces original content—blogs, videos, photos, music, or software—you automatically own the copyright. However, registering your copyright with the U.S. Copyright Office provides added legal benefits, including the ability to sue for damages in federal court.

Benefits of Copyright Registration:

- Legal proof of ownership

- Ability to seek statutory damages and attorney’s fees in court

- Public record of ownership

- Easier to license, sell, or transfer your rights

Commonly copyrighted works in NYC include:

- Website content

- Podcasts and videos

- Digital artwork

- Software code

- Marketing material

3. Patents

A patent protects inventions—machines, processes, chemical compositions, or designs. NYC is home to major players in biotech, fintech, green energy, and more—industries where patent protection is vital.

Types of Patents:

- Utility Patents: For new processes or machines

- Design Patents: For ornamental designs

- Plant Patents: For new plant varieties

Working with a New York Patent Attorney:

Patent law is complex, and even small mistakes in your application can lead to costly rejections. A qualified patent attorney in New York can help you prepare drawings, write claims, and navigate USPTO procedures effectively.

4. Trade Secrets

These are confidential business practices or formulas (think Coca-Cola’s secret recipe). To safeguard trade secrets, businesses should implement NDAs (non-disclosure agreements) and maintain secure data practices.

In NYC, where businesses share co-working spaces and collaborate with freelancers, trade secret protection is critical.

How to Protect Trade Secrets:

- Use non-disclosure agreements (NDAs) with employees, contractors, and partners

- Restrict access to sensitive data

- Implement clear internal policies for handling confidential information

Unlike patents, trade secrets do not expire as long as they remain confidential.

Source: gettyimages.com

Why IP Law Protection Matters in NYC

NYC’s business environment is a challenge. With a diverse and saturated market, having exclusive rights to your intellectual assets allows you to:

- Establish brand identity

- Prevent imitation and infringement

- Attract investors and funding

- Create licensing opportunities

- Enhance company valuation during mergers or acquisitions

Imagine investing years into developing a proprietary software platform or building a recognizable logo, only to have a competitor replicate it. Without legal IP protection, your business could lose revenue, trust, and market share.

The Challenges of Protecting IP Law in NYC’s Competitive Market

New York City’s entrepreneurial energy is unmatched—but so is the competition. Entrepreneurs face unique challenges, including:

- Brand imitation by local competitors

- Unauthorized use of copyrighted content online

- Patent disputes in the tech and biotech industries

- Theft of proprietary information by former employees or partners

This is why consulting with a New York IP law firm early in the business lifecycle is vital. IP attorneys can help draft licensing agreements, enforce IP rights, and handle litigation if necessary.

Steps to Take for Effective IP Law Protection in NYC

1. Perform an IP Audit

Evaluate what intellectual property your business owns or is developing. This includes checking for existing trademarks, patented inventions, proprietary content, or confidential processes.

2. Register Your IP

While some IP rights arise automatically, registering with the appropriate government bodies (USPTO, Copyright Office) strengthens your legal standing.

3. Create Legal Agreements

Protect your business with contracts such as:

- Non-disclosure agreements (NDAs)

- Work-for-hire contracts for creatives

- Licensing agreements

- Partnership agreements outlining IP ownership

4. Monitor for Infringement

Use monitoring tools or work with an IP lawyer to regularly check for unauthorized use of your trademarks, content, or inventions.

5. Enforce Your Rights

Don’t let IP violations slide. NYC’s legal system offers multiple avenues for enforcement—from cease and desist letters to full-blown litigation.

How an IP Law Firm in NYC Can Help

Partnering with an intellectual property law firm in NYC provides tailored legal strategies that align with your business goals. Whether you’re launching a tech startup, running a fashion label, or developing creative content, a local IP attorney understands the nuances of NYC’s regulatory and business environment.

Services may include:

- Trademark and patent registration

- Drafting contracts and licensing agreements

- IP litigation and dispute resolution

- Trade secret protection strategies

Final Thoughts:

In a city where competition is fierce and innovation is constant, navigating intellectual property law isn’t optional; it’s critical. By understanding your rights, registering your assets, and partnering with a trusted legal expert, you can protect your creative capital and gain a competitive edge in NYC’s dynamic business ecosystem. The Law Firm of Dayrel Sewell, PLLC is a leading intellectual property law firm in New York, dedicated to helping innovators, entrepreneurs, and businesses safeguard their ideas and maximize their value. Trust our experience to protect what matters most, your intellectual property.