Ever since Pheidippides ran from Marathon to Athens, athletes of all levels have marveled at the pursuit of running a marathon.1 26.2 miles is an incredibly daunting task, and professionals to amateurs alike have learned to respect the distance – the race does not owe anyone anything. The allure of competitive racing is the act of accomplishing something that many others cannot, as well as breaking personal barriers and records. For years, feats in professional distance running saw few advances and many runners were reaching unbreakable plateaus using the same shoes they’ve been wearing for years (with very minor advances in shoe technology). However, in recent years, many big players in sportswear have begun to develop what are now being called “super shoes.”2 Basically, this category of running footwear is inclusive of any shoe that is meant to be fast and lightweight with enough cushion and bounce to propel your next step to the finish.3 However, it is the implementation of a few more specific attributes that has garnered attention from runners, coaches, and sports journalists worldwide – carbon plates and engineered mesh upper.4 The addition of this plate, along with lightweight yet stable uppers, allows for a greater energy return during a runner’s stride and was marketed to have increased running economy by roughly over 4%, hence Nike’s naming of their shoe to be the “Vaporfly 4%.”5

Runners in Nike’s Vaporfly & Alphafly

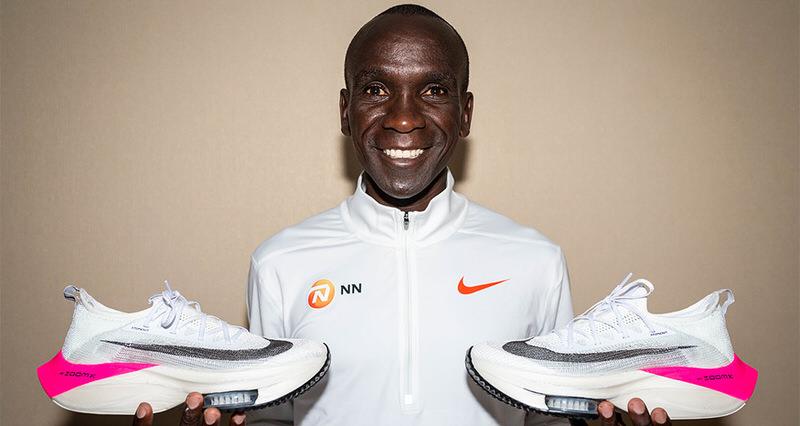

Super shoes are highly controversial by their very nature, and many consider them to be a form of “mechanical doping.”6 Mechanical doping has been at the subject of controversy in other endurance sports like swimming and cycling, as products in production have been banned for the unfair advantages that they offer the athletes who use them.7 Further, many regulations have needed to be put into place to prevent and monitor this form of “doping” by sports and rules federations around the globe.8 The advantages these super shoes offer to runners are no exception, as they seem highly unfair to runners who compete without them and almost appear illegal. In fact, Nike’s original Vaporfly model was banned from competition initially.9 Professional marathon runner and motivational athlete Eliud Kipchoge broke the all-time world record for his sub 2-hour marathon time in one of Nike’s super shoes, the Alphafly Next%10, and many athletes and critics were quick to discredit his time and overlook his race as a result almost entirely obtained because of his shoes.11 The reasoning adopted by these critics, albeit flawed12, does have roots in a serious issue regarding those shoes. The main reason for this argument was because, at the time, Nike was the only player in the sport making sneakers at this caliber and with this level of new technology.13 Their running shoe technology was groundbreaking, and non-Nike sponsored athletes were surely paying the price.14 Athletes at all levels that were not sponsored by Nike could not seem to catch a break, as, until recently, athletes at the podium were all sporting Nike running shoes alongside their medals and accolades. But now, seemingly every competing sportswear company that produces high-level running shoes is releasing models that can compete with Nike’s. Nike is still considered the mecca of running shoe producers to many, yet various athletes are breaking records and out-running Nike athletes in non-Nike shoes.15 Now, Nike is fighting back to remain at the top of the super shoe food chain.16

Eliud Kipchoge with Alphafly Next%’s

To very little surprise, the most popular competitor for Nike in this running shoe arms race is Adidas. The Checks vs. Stripes feud seems to date back nearly as far as Nike’s inception itself.17 You can imagine Adidas’ frustration when a company decades younger has soared to the top of nearly every sports market.18 But Adidas has been able to rival Nike’s Vaporfly and Alphafly models with the introduction of the Adidas Adios Pro line.19 These Adidas shoes are made using Primeknit technology, while Nike’s are made using patented Flyknit technology, and this is where the issue lies.20 Nike claims that Adidas has stolen their “game-changing” technology for various product designs, seeking injunctive relief as well as monetary damages.21 Before this complaint filed by Nike, Adidas lost in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit to Nike after alleging that Nike violated two patents owned by Adidas.22 As part of their request for injunctive relief, Nike has further requested that the U.S International Trade Commission block all imports of various Adidas shoe models that allegedly infringe on Nike’s patented designs and technology.23 These patents that Nike seeks to protect are some of the most crucial aspects to the Vaporfly and Alphafly designs, as they allow the shoe to be extremely lightweight and comfortable, which in turn increases running performance in users.24 This technology is constantly being improved upon and changed, so it is uncertain whether these patent disputes are worth it for these companies in the long term, but for now they do not appear to be going away. Nike will attempt to protect their designs to stay on top, while Adidas will fight to remain as competitive as they can be as a late player to the game. While many other running brands, like Asics25, have developed a more unique model of super shoe, it is notable that Nike and Adidas are seemingly the only players that wish to compete not only with the entire market, but with each other in a separate battle to the finish.

Nike Alphafly Next% vs. Adidas Adios Pro

It is difficult to deny the extent and breadth of Nike’s impact on sportswear and the running world.26 While their competitive edge remains prevalent, many new players in the game of elite super shoe production seem to be startling the industry leader. It will be very interesting to see how this case ultimately plays out, as it will set important precedents in running shoe technology advances as super shoes only seem to be getting better and better with each new model. Moreover, it will be just another landmark case in the ongoing battle between Nike and Adidas to see who truly reigns supreme as the top sportswear brand.27

As this case continues, and as progressively more people pick up competitive racing as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic28, it is likely for us to see many similar complaints and cases regarding running shoe technology begin to develop. And it makes sense – superpower companies will always try to protect technology and products that they believe to be proprietary and top-notch, and smaller corporations will always fight to remain competitive in a market dominated by only a fraction of the total players. As of July 2022, Adidas and Nike are both set to release brand new models of their super shoes, the Adizero Adios Pro 3 and the Alphafly Next% 3 respectively, before the Fall 2022 marathon season.29 This will indeed make for a very interesting sneaker battle come time for the results of the fall circuit, and possibly the king of super shoes will be crowned once and for all.

1See Dean Karnazes, The Real Pheidippides Story, Runner’s World (Dec. 6, 2016), https://www.runnersworld.com/runners-stories/a20836761/the-real-pheidippides-story/.

2Jonathon Taylor, Super shoes: Explaining athletics’ new technological arms race, The Conversation (Mar. 2, 2021, 7:47 AM), https://theconversation.com/super-shoes-explaining-athletics-new-technological-arms-race-156265.

3See Jonathon Taylor, Super shoes: Explaining athletics’ new technological arms race, The Conversation (Mar. 2, 2021, 7:47 AM), https://theconversation.com/super-shoes-explaining-athletics-new-technological-arms-race-156265; Bryce Dyer, Nike Vaporfly ban: why World Athletics had to act against the high-tech shoes, The Conversation (Feb. 6, 2020, 6:50 AM), https://theconversation.com/nike-vaporfly-ban-why-world-athletics-had-to-act-against-the-high-tech-shoes-131249.

4E.g. Jonathon Taylor, Super shoes: Explaining athletics’ new technological arms race, The Conversation (Mar. 2, 2021, 7:47 AM), https://theconversation.com/super-shoes-explaining-athletics-new-technological-arms-race-156265.

5Id.

6E.g. THE CURIOUS CASE OF MECHANICAL DOPING, Sneaker Speculation (May 7, 2020), https://sneakerspeculation.com/2020/05/07/the-curious-case-of-mechanical-doping/.

7See id.

8See id.

9E.g. Stuart Greenwood, Kicking up a storm – a breakdown of Nike’s ground-breaking and controversial range of running shoes, AA Thornton (Feb. 2020), https://www.aathornton.com/nike-vaporfly/; Wall Street Journal, The Controversy Behind Nike’s Vaporfly Running Shoe, Explained | WSJ, YouTube (Jan. 23, 2020), https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wVXrIaPuP7c.

10Luis Torres, How Eliud Kipchoge and the Nike AlphaFly Made History, Nice Kicks (Oct. 14, 2019), https://www.nicekicks.com/how-eliud-kipchoge-and-the-nike-alphafly-made-history/.

11See James Witts, Technological doping: The science of why Nike Alphaflys were banned from the Tokyo Olympics, Science Focus (Sept. 4, 2021, 4:00 PM), https://www.sciencefocus.com/the-human-body/nike-alphafly-banned-technological-doping/.

12See Brian Metzler, Banning Kipchoge’s Shoes Is the Dumbest Take in Running Right Now, Runner’s World (Oct. 21, 2019), https://www.runnersworld.com/gear/a29533576/ban-kipchoge-nike-shoes-vaporfly/.

13E.g. Running shoe tech: The Emperor’s clothes, and the issues for the integrity of running, The Science of Sport (Feb. 6, 2020), https://sportsscientists.com/2020/02/running-shoe-tech-the-emperors-clothes-and-the-issues-for-the-integrity-of-running/.

14THE CURIOUS CASE OF MECHANICAL DOPING, Sneaker Speculation (May 7, 2020), https://sneakerspeculation.com/2020/05/07/the-curious-case-of-mechanical-doping/.

15See Tony Owusu, Adidas Runs Into Nike FlyKnit Patent Lawsuit, TheStreet (Dec. 10, 2021, 9:18 AM), https://www.thestreet.com/investing/nike-sues-adidas-flyknit-patent.

16E.g. Rachel Bernardo, How Adidas Develops Adizero For World Record Performances, Believe In The Run (Apr. 21, 2022), https://www.believeintherun.com/adidas-adizero-roads-to-records/.

17NIKE VS ADIDAS: A CLASH OF GIANTS TO DOMINATE THE SNEAKER MARKET, AIO bot (Oct. 6, 2017), https://www.aiobot.com/nike-and-adidas-fight/.

18Id.

19See Brandon Law, Comparison: Nike Alphafly Next% vs Adidas Adizero Adios Pro, Running Shoes Guru (last visited July 6, 2022), https://www.runningshoesguru.com/comparison/nike-alphafly-next-vs-adidas-adizero-adios-pro/.

20Id.

21Id.

22See Blake Britian, Nike asks U.S. agency to block Adidas shoe imports, citing patents, Reuters (Dec. 9, 2021, 12:16 PM), https://www.reuters.com/legal/transactional/nike-asks-us-agency-block-adidas-shoe-imports-citing-patents-2021-12-09/; Brendan Pierson, IN BRIEF: Nike prevails in shoe patent dispute with Adidas, Reuters (June 25, 2020, 6:57 PM), https://www.reuters.com/article/ip-nike/in-brief-nike-prevails-in-shoe-patent-dispute-with-adidas-idUSL1N2E22SN.

23Id.

24Tony Owusu, Adidas Runs Into Nike FlyKnit Patent Lawsuit, TheStreet (Dec. 10, 2021, 9:18 AM), https://www.thestreet.com/investing/nike-sues-adidas-flyknit-patent.

25Cory Smith, ASICS Challenges Nike Super Shoe With ‘MetaSpeed Sky’: Review, Gear Junkie (Mar. 29, 2021), https://gearjunkie.com/footwear/asics-metaspeed-sky-running-shoe-review.

26E.g. id.

27See Nike vs Adidas Case Study: Who Is Winning? All You Need To Know, 440 Industries (Sept. 23, 2021), https://440industries.com/nike-vs-adidas-case-study-who-is-winning-all-you-need-to-know/.

28Wings for Life World Run, Running becoming increasingly popular, Red Bull (Jan 2, 2021), https://www.redbull.com/in-en/running-becoming-increasingly-popular.

29See Taylor Willson, NIKE VS ADIDAS: BATTLE OF THE “SUPER SHOE”, Highsnobiety (June 15, 2022), https://www.highsnobiety.com/p/nike-alphafly-next-2-adios-pro-3-super-shoe-info/.