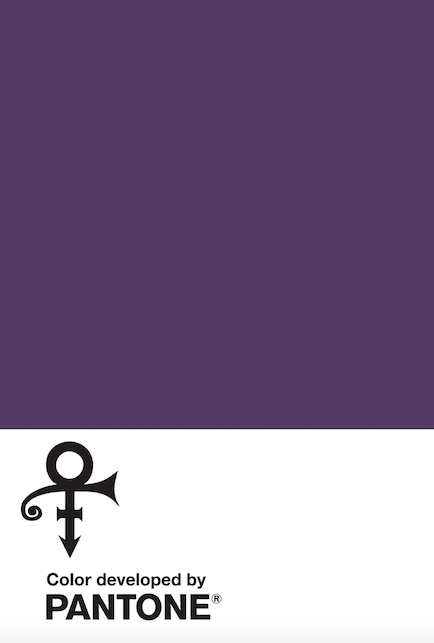

In October 2018, Paisley Park Enterprises filed an application with the USPTO (U.S. Patent and Trademark Office) for the registration of a color mark for music, live performance, and museum-related uses [1]. Paisley Park Enterprises is known for being decedent Prince Rogers Nelson’s company. In August 2017, the Prince Estate and Pantone created a purple color called “Love Symbol #2” to represent Prince [2]. The Pantone Matching system is useful to define particular shades of color, and to ensure a consistent use of the same color for one company [3].

In 1985, U.S. courts held that colors could be protected under trademark law [4]. Owens-Corning was the first company in the U.S. to hold a color mark. The fact that colors can be protected by a trademark is a natural expansion of trademark law since trademark may protect words, logos, sounds, designs, smells, and other designations [5].

To be protectible under trademark law, a mark has to be distinctive. A mark can be inherently distinctive if that mark is fanciful (an example would be a made-up or invented word, such as Exxon), arbitrary (a mark having no relationship with the goods or services being sold, for example Apple for computers), or suggestive (it requires imagination from the consumer to reach a conclusion as to the nature of the goods or services, for example Mustang for cars). If a mark is descriptive, it is not inherently distinctive and a showing of secondary meaning is required in order to be protectible. In the Qualitex case, the U.S. Supreme Court held that colors could be distinctive and protected under trademark law, but the court specified that a color can never be inherently distinctive. Since a color cannot be inherently distinctive, the applicant for a color mark is always required to show secondary meaning [6]. To establish secondary meaning, an applicant must show that the consumers associate the mark to the source of the product or services, and not to the products or services themselves [7]. In other words, the applicant must show that the mark is a source identifier.

The secondary meaning requirement may be justified by the argument that the number of possible colors to be used by competitors could be greatly diminished if the courts and the USPTO were to give trademark rights too easily on trademark applications for color marks. A requirement of secondary meaning limits that possible depletion of the possible colors to be used. Courts may be reluctant to give trademark protection for color marks too lightly, since in some instances there might be underlying reasons behind the use of certain colors. An example is the color orange for safety-related companies and products. Another possible issue is the idea of shade confusion, courts may have difficulties in determining which colors are similar enough to constitute a trademark infringement, and which are not.

Functionality is a bar to trademark protection. If a mark is functional, it can not be protected under trademark law, even if the mark holder would have been able to show secondary meaning. The courts use two tests in order to determine whether a mark is functional or not. A mark is functional under the first test (known as the Qualitex test) if the exclusive use of the mark would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage [8]. Under the second test (the Inwood test), a feature is functional if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article, or if it affects the article’s cost or quality [9]. To be non-functional, a mark has to be non-functional under both tests. The concept of aesthetic functionality, absent from the statutes but recognized by virtually every court in the U.S., is also a possible barrier to the registration of a color mark. This concept applies in the case of features which have no functional utility, but that consumers want, often for aesthetic reasons. In most cases relating to aesthetic functionality, the first test of functionality is satisfied as an exclusive use would put competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage, and the mark is then deemed functional. A color mark may be functional in some instances according to this aesthetic functionality concept.

In a case opposing Christian Louboutin to Yves Saint Laurent, courts held the trademark protection on Christian Louboutin’s red sole to be enforceable, but that this protection only covered shoes when the red sole contrasted with the upper of the shoe [10]. That protection is thus limited and does not extend to the manufacture and sale of monochrome red shoes with a red sole, such as the red Yves Saint Laurent’s shoe at issue. This decision allowed Louboutin to benefit from trademark protection on its red sole without putting its competitors at a significant non-reputation-related disadvantage.

The USPTO refused to register Paisley Park Enterprises’ “Love Symbol #2” mark because consumers do not perceive this color as a source identifier according to the USPTO. The USPTO noted that album covers from other artists such as Cam’ron and Kanye West also included the use of the color purple, and that the purple color was not distinctive of Paisley Park Enterprises’ products and services as it is a commonly used color in the sale of products and services in the same class. [11]

Color is often used as a source identifier by companies. Tiffany’s Robin’s Egg blue color, which is used on their boxes, is protected by a trademark, the Tiffany Blue hue has been held to be distinctive through an acquired secondary meaning. UPS also registered its brown color as a trademark [12]. Paisley Park Enterprises may try to show that the particular purple color they are trying to register serves as a source identifier, and they may argue that consumers associate this purple color to Prince. If Paisley Park Enterprises manages to show secondary meaning, the USPTO will be likely to accept the registration of the “Love Symbol #2” color mark.

[1] http://www.thefashionlaw.com/home/princes-estate-is-seeking-federal-trademark-protection-for-his-purple-pantone-hue

[2] https://www.pantone.com/about/press-releases/2017/the-prince-estate-and-pantone-unveil-love-symbol-number-2

[3] https://www.ipwatchdog.com/2018/07/14/can-you-trademark-a-color/id=99237/

[4] In re Owens-Corning Fiberglas Corp., 774 F.2d 1116 (Fed. Cir. 1985)

[5] Restatement of the Law (Third), Unfair Competition : §9 Definitions of TM and service mark

[6] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995)

[7] https://tmep.uspto.gov/RDMS/TMEP/current#/current/TMEP-1200d1e10316.html

[8] Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Products Co. Inc., 514 U.S. 159 (1995)

[9] Inwood Laboratories Inc. v. Ives Laboratories, Inc., 456 U.S. 844 (1982)

[10] Christian Louboutin, SA v. Yves St. Laurent America Holding, Inc, 709 F.3d 140 (2d Cir 2013)

[11] http://www.thefashionlaw.com/home/us-trademark-body-says-prince-was-not-the-only-musician-to-make-use-of-the-color-purple

[12] https://www.ups.com/media/en/trademarks.pdf