A jury’s job throughout a trial is to comprehend, understand and process all of the information conveyed by both the attorneys and witnesses. Plainly hearing this information without any form of aids (e.g., picture, graphs, physical objects, etc.) can lead to forgetfulness when it comes time for deliberations. That is why it has been common practice in the trial world to use evidence to help these juries pair aids with facts throughout a trial. Lawyers are afforded the ability to use demonstrative and substantive evidence throughout the presentation of their case: both to simplify information and make it more memorable. Demonstrative evidence is used to give the jury a chance to experience the issues and facts of a case in the eyes of the presenting party. The main purpose of demonstrative evidence is to make the jury believe that your theory of the case is the one that should prevail.

What is Demonstrative Evidence?

There are three general categories of evidence recognized in trial practice: real, testimonial and demonstrative. For the purposes of this article, demonstrative and real evidence are the focus. Real evidence is considered evidence that was actually involved in the case at trial. For example, the gun that was used to commit an alleged murder, or the defective part of a product being questioned in a liability case would be considered substantive evidence. Demonstrative evidence on the other hand, is used purely to enhance oral testimony. Unlike real evidence, this type of evidence has no independent probative value because it had no part in the actual events of the case. Demonstrative evidence is solely used to help the jury understand one’s theory of the case at hand. Distinctive from substantive evidence, this type of evidence can be anything you can touch, see or hear as long as it was created for the purposes of litigation. For example, the gun that was used to commit an alleged murder, mentioned above is substantive evidence, but a computer generated image of that gun or an exact replica of that gun, used for the purpose of making the jury better understand is demonstrative. The most important distinction between real and demonstrative evidence is that real evidence can be taken into the jury room during their deliberations, while demonstrative evidence most certainly cannot. The only relevance demonstrative evidence has to a case is to help explain the facts, and to help give a witness’s testimony greater probative value. This kind of evidence does not have any independent relevance outside of that.

How is Demonstrative Evidence Admissible?

If demonstrative evidence has no independent probative value, and no objective relevance to the case, then we must wonder what rationale the courts could have for this evidence to be admissible. That answer is simple, it makes the trial easier and more entertaining for the jury to follow. It makes listening to the potentially boring and confusing testimony of multiple witnesses less boring and less confusing, thus ultimately more believable. As McCormick put it:

“Since ‘seeing is believing’, and demonstrative evidence appeals directly to the senses of the trier of fact, it is today universally felt that this kind of evidence possess an immediacy and reality which endow it with particularly persuasive effect.” [1] McCormick On Evidence §212 (E. Cleary 2d ed. 1981).

Demonstrative evidence is not automatically admissible however. The same rules of evidence that are followed to bring in substantive evidence must also be followed to bring in demonstrative evidence. The trial judge does however have immense amounts of discretion when it comes to admissibility. These requirements involve a showing of relevancy to the facts at issue and the laying of a proper foundation once the evidence is deemed relevant. To do this an attorney must show that the demonstrative evidence will be used for the purpose of either educating, simplifying or informing the jury. Both the relevancy and foundational requirements are usually met through the testimony of the witness the demonstrative evidence is meant to enhance. Because demonstrative evidence is supposed to explain a witness’s testimony, their testimony alone would bring out the relevancy. The witness can then be asked questions throughout the course of their testimony that will authenticate and therefor lay the foundation for the evidence. The main difference between the admission of demonstrative evidence in comparison to substantive evidence is that substantive evidence is required to be introduced and admitted into evidence before it can be referred to at trial. Demonstrative evidence can be displayed and referred to without being formally admitted. Although that is not suggested because then the evidence is not part of the record, and cannot be referred to on appeal.

While the requirements for admissibility of demonstrative evidence are not hard to meet the trial judge must still use a balancing test to determine whether the evidence can be used at trial. Just as with any other kind of evidence the judge must weigh the probative effect the evidence can have on explain the case against the prejudicial effect that this evidence could potentially have on the defendant. A popular example of this would be pictures of a crime scene or dead body after a murder. If the pictures are just being used to enhance the jury’s understanding of the case a judge will most likely say they are too prejudicial. However, if these pictures add something to the case, such as clarifying a dispute of the angle a person was shot, a judge would most likely conclude that the probative value outweighed the prejudicial one.

Is Demonstrative Evidence more helpful or harmful?

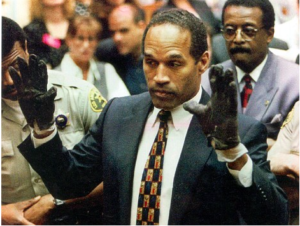

In most cases demonstrative evidence is one of the most helpful tools in the litigation book. Why wouldn’t it be, when demonstrative evidences main purpose is to help enhance the understanding of all of the evidence being thrown at the jurors. Scientifically speaking it has been shown that using visual aids combined with oral testimony can increase retention and understanding by almost 65 percent,[2] and in the mind of a juror the use of demonstrative evidence allows for some excitement and dramatic effect in what they might otherwise consider a relatively boring day. One of the greatest reminders of how influential demonstrative evidence can be stems from the infamous O.J. Simpson murder trial. Some people say O.J. Simpson wasn’t convicted because of his race, and other say that a jury was never going to convict a man of his stature, but what lawyers saw was the effective use of demonstrative evidence. Clearly, we are talking about the image of O.J. Simpson standing in front of that jury and trying on a glove that was supposed to be the same size and brand as the glove he was wearing when he killed his ex-wife. The glove did not fit and therefore diminished the prosecution’s theory and enhanced the defense’s theory, in a highly dramatic way that the jury would remember when it began deliberations. So, can demonstrative evidence be a helpful courtroom tool? Of course; it can have a huge effect on enhancing the credibility of a witness or a jury’s perception of the theory of the case in general, but as always there is a down side to the use of demonstrative evidence as well.

When making the decision to bring in demonstrative evidence a lawyer must be very careful that the potential benefits outweigh the potential harms. As stated above the potential benefits could be immense, but so could the potential harms. For example, since the judge has an extremely broad discretion in deciding what demonstrative evidence is too prejudicial and what is admissible, the use of demonstrative evidence thus opens up the door to use as an issue on appeal.

An appeal relating to demonstrative evidence can be brought for a variety of reason. For instance, the demonstrative evidence could have been too prejudicial and therefore should not have been deemed admissible. Or the demonstrative evidence could have been used incorrectly and therefore produced an erroneous verdict. This can lead to retrials and reversals, which not only lengthens the trial process, but also adds to the courts already overflowing dockets. The 7th Circuit Court of Appeals recently reversed the jury verdict in the case of Baugh v. Cuprum for this very reason. 730 F.3d 701 (2013). The case was reversed for improper use of demonstrative evidence, because the evidence was allowed into the jury room during deliberations. Erroneous use of demonstrative evidence can easily become a widespread and persistent problem, due to the ambiguity in the definition and instruction on the use of demonstrative evidence. The lack of uniformity throughout the court system can also add to this problem, because of the trial judge’s discretion pertaining to the ways in which demonstrative evidence can be used varies between circuits and therefore leads to inconsistent case results within the court system.

This leaves us with the question of whether demonstrative evidence should continue to be used in trial practice, and the answer is yes. While it is true that a lawyer opens the case up to greater chance of objections and reversal on appeal the helpfulness of the evidence outweighs that the potential negatives. Not only does it make a trial more interesting and more dramatic, but it also increases the likelihood that the jury pays better attention. It also helps the jury to actually understand the facts of the case, which can ultimately lead to more informed decision making. Although there can never be a guarantee that the jury will correctly apply the facts to the law and return with the right verdict, the effective and skilled use of demonstrative evidence during trial makes it more probable.

[1] Stephen P Lindsey, “Do You Hear What I Hear?” Why Demonstrative Evidence Makes a Difference, Fed. CJA Trial Skills Academy (2010).

[2] Karen D. Butera, Seeing Is Believing: A Practitioner’s Guide to the Admissibility of Demonstrative Computer Evidence, 46 Clev. St. L. Rev. 511, 513 (1998).