“First-Sale” Resellers Rejoice

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

KIRTSAENG, DBA BLUECHRISTINE99 (Petitioner) v. JOHN WILEY & SONS, INC. (Respondent)

No. 11–697. Argued October 29, 2012—Decided March 19, 2013

COMMENT

Recently, a seminal decision was issued by the Supreme Court of the United States that undoubtedly affects the scope of rights for copyright holders as well as the resellers of those copyrighted works.

Background

John Wiley & Sons, Inc., an academic textbook publisher, often assigns to its wholly owned foreign subsidiary (Wiley Asia) rights to publish, print, and sell foreign editions of Wiley’s English language textbooks abroad. Wiley Asia’s books state that the books are not to be taken (without permission) into the United States.

Supap Kirtsaeng moved to the United States from Thailand in 1997 to pursue an undergraduate degree in mathematics at Cornell University. After moving, Kirtsaeng asked friends and family to buy foreign edition English-language textbooks in Thai book shops, where the books were sold at low prices, and to mail the books to him in the United States. He then sold the books, reimbursed his family and friends, and kept the profit. Allegedly, in this manner, Kirtsaeng subsidized the cost of his education.

Issue

Whether the “first sale” doctrine should apply to copies of a copyrighted work lawfully made abroad.

Procedural Posture

On September 8, 2008, Wiley brought suit against Kirtsaeng in the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York. Wiley filed suit, claiming—amongst other things—that Kirtsaeng’s unauthorized importation and resale of its books was a copyright infringement of Wiley’s 17 U.S.C. § 106(3) exclusive right to distribute and 17 U.S.C. §602’s import prohibition.

Kirtsaeng retorted that because his books were lawfully made and acquired legitimately, 17 U.S.C. §109(a)’s “first sale” doctrine permitted importation and resale without Wiley’s further permission.

The District Court jury ultimately found Kirtsaeng liable for willful copyright infringement of all eight works and imposed damages of $75,000 for each of the eight works. The District Court held that Kirtsaeng could not assert this defense because the doctrine does not apply to goods manufactured abroad. Kirtsaeng appealed.

On August 15, 2011, in a 2-1 split decision, the Second Circuit affirmed the District Court’s ruling, concluding that §109(a)’s “lawfully made under this title” language indicated that the first sale doctrine does not apply to copies manufactured outside of the United States.

On April 16, 2012, petition for writ of certiorari to the Second Circuit was granted by the Supreme Court.

Discussion

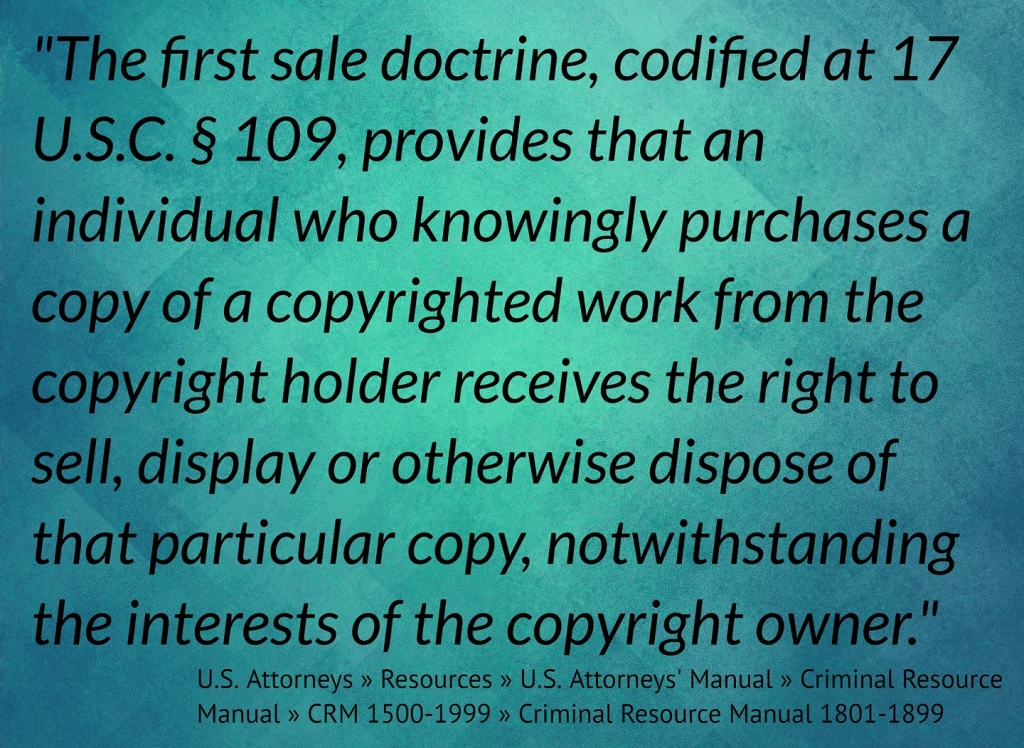

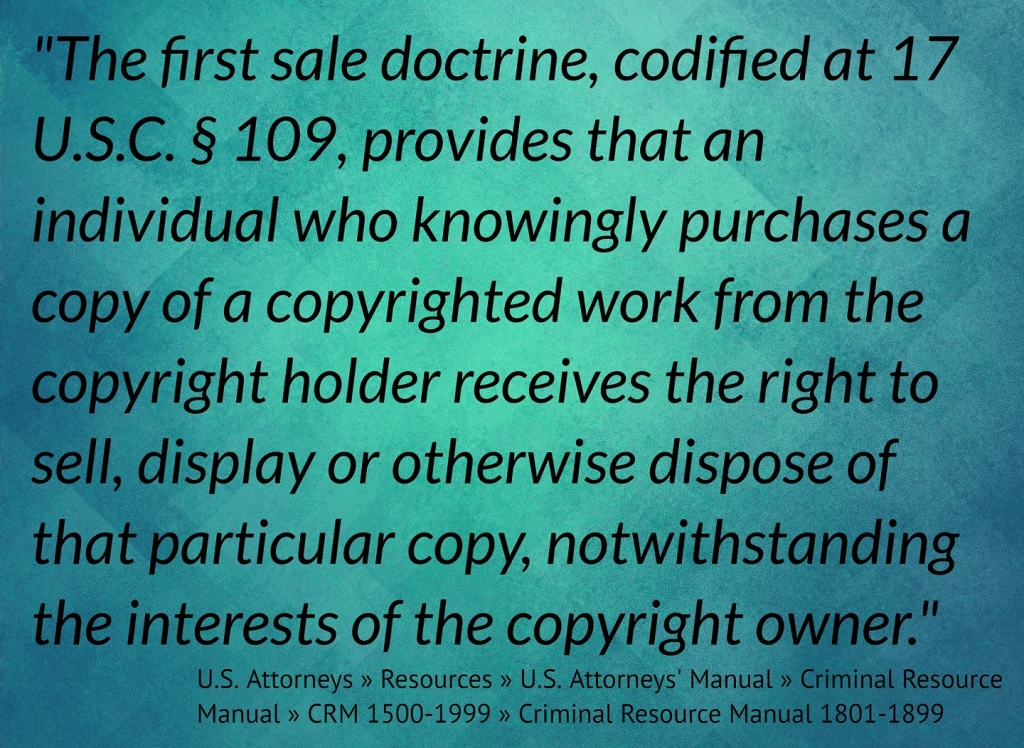

The first sale doctrine is codified at 17 U.S.C. § 109(a). Section 109(a) reads, in relevant part,:

Notwithstanding the provisions of section 106(3) [of the Copyright Act], the owner of a particular copy … lawfully made under this title, or any person authorized by such owner, is entitled, without the authority of the copyright owner, to sell or otherwise dispose of the possession of that copy….

The crux of the argument between the litigants is the imposition, or lack thereof, of geographical limitations vis-à-vis the statutory language of “lawfully made under this title”. Should Wiley’s argument of geographical limitations apply to this statutory language, it would mean that the first-sale doctrine does not apply to Wiley Asia’s books. Contrastingly, should Kirtsaeng’s argument of non-geographical limitation made “in accordance with” or “in compliance with” the Copyright Act, then the first-sale doctrine would apply to copies manufactured abroad and could be re-sold without the copyright owner’s permission.

The Court first analyzed § 109(a)’s statutory language and held that § 109(a) says nothing about geography. A non-geographically based, simple reading “promotes the traditional copyright objective of combatting [sic] piracy and makes word-byword linguistic sense.”

Next, the Court grappled with the historical and contemporary statutory context of the language at issue. The Court held that the comparison of the language between §109(a)’s predecessor and the present provision supports the conclusion that Congress did not have geography in mind when writing the present version of §109(a). The Court also found support for its non-geographical interpretation of the first-sale doctrine predicated on Congress’ intent to retain the substance of common-law “first sale” doctrine.

Lastly, the Court relied on a constitutional law provision, which is a tenet of intellectual property law. The Court highlighted several ways that—by requiring geographical limitations—would fail to further basic constitutional copyright objectives, in particular “promot[ing] the Progress of Science and useful Arts,” U. S. Const., Art. I, §8, cl. 8.

For example: “Technology companies tell us that “automobiles, microwaves, calculators, mobile phones, tablets, and personal computers” contain copyrightable software programs or packaging. Brief for Public Knowledge et al. as Amici Curiae 10. See also Brief for Association of Service and Computer Dealers International, Inc., et al. as Amici Curiae 2. Many of these items are made abroad with the American copyright holder’s permission and then sold and imported (with that permission) to the United States. Brief for Retail Litigation Center, Inc., et al. as Amici Curiae 4. A geographical interpretation would prevent the resale of, say, a car, without the permission of the holder of each copyright on each piece of copyrighted automobile software.”

Moreover, said the Court, “reliance upon the “first sale” doctrine is deeply embedded in the practices of those, such as booksellers, libraries, museums, and retailers, who have long relied upon its protection. Museums, for example, are not in the habit of asking their foreign counterparts to check with the heirs of copyright owners before sending, e.g., a Picasso on tour. Brief for Association of Art Museum Directors 11–12.”

In summation, the Court held that Section 109(a)’s language, its context, and the “first sale” doctrine’s common-law history favored Kirtsaeng’s position.

Policy Implications

The Court, in siding with Kirtsaeng, noted “the evergrowing importance of foreign trade to America.” This 6-3 nod to being mindful of foreign trade is not to be overlooked. When the Court spoke of the activities of associations of libraries, used-book dealers, technology companies, consumer-goods retailers, and museums that would be hampered by geographical limitations, it took the important step of applying the law to the facts, and not doing so in a vacuum because of the real-world applications that Supreme Court decisions have. Will the market for reselling significantly change (i.e., supply and demand economics)? What effect will the Kirtsaeng decision have on domestic and international pricing of copyrighted works? Time will tell how the actions of copyright holders and resellers change because of the Kirtsaeng decision.

Read between the lines. It is clear that the Court weighed and balanced various factors in its decision that Wiley’s perceived benefits of the imposition of geographical limitations are far outweighed by the negative affects on foreign trade and the suppression of the progress of science and the useful arts that such geographical limitation would render.

Conclusion

The Supreme Court, in a 6-3 ruling authored by Justice Breyer, reversed the ruling of the Second Circuit Court of Appeals and remanded the case.

Held: The “first sale” doctrine applies to copies of a copyrighted work lawfully made abroad.