by Augustus Balasubramaniam, Esq.

Contracts Overview

In New York, for a legally enforceable agreement to exist at contract, the Plaintiff must establish an offer, acceptance of that offer, consideration moving between the parties, mutual assent, and intent to be bound. See Kwalchuk v. Stroup, 61 A.D.3d 118, 121 (1st Dep’t 2009). An Offer is defined as “…the manifestation of willingness to enter into a bargain, so made as to justify another person in understanding that his assent to that bargain is invited and will conclude it” (see Restatement (Second) of Contracts §24). “…(I)t must create a reasonable understanding in the offeree that the offeree has the power to create a contract by simply manifesting an assent to the offer…” See Dr. John E. Murray, Jr., Corbin on Contracts (Desk Edition 2015) § 1.05.[2] Acceptance of an Offer is a “…manifestation of assent to the terms thereof made by the offeree in a manner invited or required by the offer…” See Restatement (Second) of Contracts §50 (1). Acceptance can be by performance or a promise to perform[1], if the offer invited such mode of acceptance. Acceptance must be a voluntary act on the part of the offeree. Consideration is the bargained for exchange moving between the parties.[2] Generally, in an arms length bargain, the Courts will not inquire into the adequacy of consideration[3]. However, the bargained for exchange must move between the parties simultaneously, meaning generally, consideration must not be something done in the past, or something the party is already legally obligated to do[4]. Lastly, for an enforceable agreement to exist, it must meet the requirements of the Statute of Frauds.[5]

Breach of Contract

A Breach of contract occurs, when performance of the contractual obligations is due, but one or more of the parties to that contract fails to perform their obligations. “…[A] contract is not breached until the time set for performance has expired…” See Cole v. Macklowe, 64 A.D.3d 480, 480 [1st Dep’t 2009]. Alternatively, anytime before performance is due, if a party makes a clear, and unambiguous statement of an intent not to perform, or from that party’s conduct, it can be reasonably deduced that the party does not intend to perform, there is anticipatory breach of the contract. The party to whom performance is due may have recourse to remedies at this point in time, not withstanding performance is due sometime in the future.[6]

Remedies

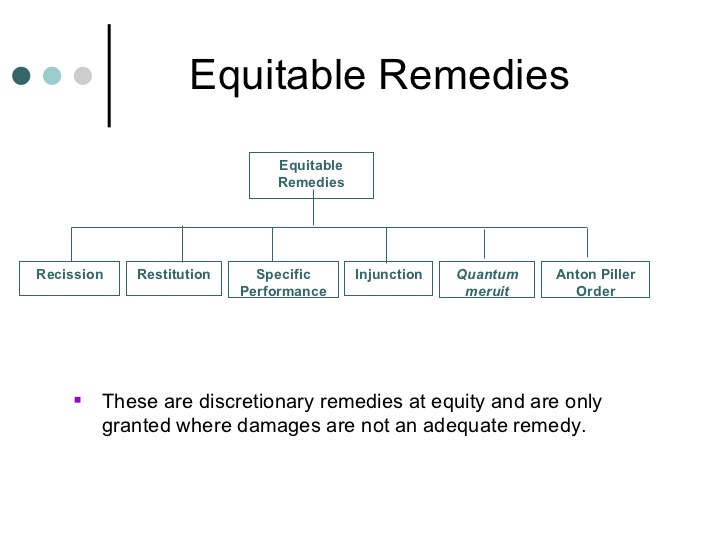

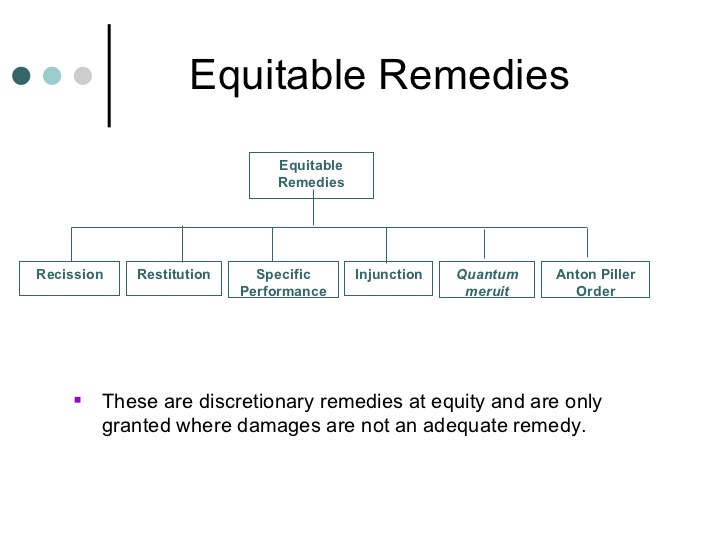

Generally, a party that suffers a loss due to a breach of contract may sue for remedies under law or equity. The most common type of remedy under the law would be damages. Providing it is foreseeable, the law will afford the aggrieved party monetary damages, the measure generally, being to put the aggrieved party in the position as if the contract had taken place. See Restatement (Second) of Contracts §§ 344-352 et al. If, on the other hand, the facts of the case dictate that damages are not feasible, equity may step in to afford what is known as an equitable remedy such as specific performance or injunction. This is especially so in real property contracts, or contracts where the subject matter of the contract is a unique good. It should be noted however that specific performance will not be available to compel individual performance of a contract due to constitutional issues that arises, specifically the 13th Amendment of the U.S. Constitution, thus varying somewhat from other common law jurisdictions. See Vanderbilt University v. DiNardo, 174 F.3d 751 (6th Cir. 1999).

Implications for Equitable Remedies in Day-to-Day Practice

It is not uncommon, when an attorney drafts a pleading for a breach of contract case, to see a wrongly chosen remedy, which sometimes could be fatal to the litigation at issue. It is essential therefore that attorneys ensure the remedy chosen fit the elements of the remedy they seek, and which in turn applies to the facts of the case. This is especially true when attorneys are faced with a situation in their clients’ cases where there is no clear remedy in law. Courts are varied in their approach to the grant of equitable remedies for breach of contract. While, generally, it could be agreed the courts will look at ‘all the circumstances of the case’, and if it is ‘just and equitable’ to grant equitable relief in the case, what that means in practice will vary greatly. Drafters of contracts include what is known as “equitable relief clauses” in contracts in the hopes, at least to some extent, to try to limit the uncertainty surrounding the grant of equitable relief by the courts. Some jurisdictions such as Delaware, interpret equitable relief clauses in contracts as giving rise to a presumption of irreparable harm, a factor to be established by the plaintiff in order to succeed in getting equitable relief from the courts. See Gildor v. Optical Sols., Inc., No. 1416-N, 2006 WL 4782348 (Del. Ch. June 5, 2006). Other jurisdictions, including The Federal Courts, on the other hand, place very little-to-no weight to these equitable relief clauses in contracts. See La Jolla Cove Inv’rs, Inc. v. GoConnect Ltd., No. 11CV1907 JLS JMA, 2012 WL 1580995 (S.D. Cal. May 4, 2012). See also Smith, Bucklin & Assocs., Inc. v. Sonntag, 83 F.3d 476, 478 (D.C. Cir. 1996). Our own courts here in New York have taken the middle ground in cases that have come before them in relation to the equitable relief clauses in contracts. The courts have shown willingness to consider the existence of the said clauses in their overall analysis of whether equitable relief should be granted. See Imprimis Investors LLC v. Indus. Imaging Corp., QDS 22701503, 2008 N.Y. Misc. LEXIS 7384, at *16–17 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. Sept. 7, 2008). See also Gramercy Warehouse Funding I LLC v. Colfin JIH Funding LLC, No. 11 CIV. 9715 KBF, 2012 WL 75431 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 6, 2012).

Is breach of contract illegal?

Breach of contract itself, per se, is not illegal in New York. A breach of contract occurs when one party fails to fulfill their obligations under a legally binding agreement without a valid excuse. However, when a breach of contract happens, the non-breaching party has legal remedies available to them. They can sue the breaching party for damages, specific performance (forcing the breaching party to fulfill their obligations), or other appropriate remedies as specified in the contract or allowed by law. Legal consequences arise from the failure to fulfill contractual obligations, rather than the breach itself being illegal. It’s important to consult with a qualified attorney for specific legal advice related to contract disputes in New York or any other jurisdiction.

Bottom line is, when dealing with breach of contract cases seeking equitable relief; it is prudent for the practitioner to ensure airtight arguments to further their client’s case. The old English saying from some 350 years ago, which articulated a common complaint amongst the legal practitioners of yesteryear, to some extent, holds true even today…‘Equity is a roguish thing. For Law we have a measure, know what to trust to; Equity is according to the conscience of him that is Chancellor, and as that is larger or narrower, so is Equity. ‘T is all one as if they should make the standard for the measure we call a “foot” a Chancellor’s foot; what an uncertain measure would this be! One Chancellor has a long foot, another a short foot, a third an indifferent foot. ‘T is the same thing in the Chancellor’s conscience. See Edward Fry, Life of John Selden, in “Table Talk of John Selden” (Fredrik Pollock edition, 1927) at page 177.

[1] See Restatement (Second) Contracts §§50 (2), (3), 53-54.

[2] See Restatement (Second) Contracts §71.

[3] See Moezinia v. Ashkenazi, 136 A.D.3d 988 [2d Dep’t 2016].

[4] See Braka v. Travel Assistance Intern., 25 A.D.3d 456 [1st Dep’t 2006].

[5] Contracts for goods of $500 and more are covered by the Uniform Commercial Code which mirrors the Statute of fraud provisions.

[6] See O’Connor v. Sleasman, 37 A.D.3d 954, 956 [3d Dep’t 2007].