In the recent article “Statutory Violations Not Enough to Give Rise to a Cause of Action for Class Actions says U.S. Supreme Court“, we have analyzed the high-profile case TransUnion v. Ramirez and, specifically, the Supreme Court’s reasoning on the standard of proving tort damages in class actions. The full article with a detailed analysis of the case is available via the link above.

In this comment, we would like to elaborate on the privacy implications of TransUnion v. Ramirez and, in particular, analyze the post-TransUnion case law of the Second Circuit from the perspective of privacy laws.

- The Factual Analysis

To briefly summarize the facts of the case1: A credit reporting agency, TransUnion, was sued by Sergio Ramirez who was denied from buying a car because he was on a “terrorist list” according to the consumer report provided by TransUnion.

The issue is that TransUnion’s software aimed to facilitate the compilation of personal and financial information about individual consumers (OFAC Name Screen Alert) generated many false positives because many consumers shared names with those included in the OFAC list.

In this respect, Ramirez filed a class-action lawsuit alleging TransUnion’s alleging that it violated the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) by failing to follow reasonable procedures to ensure the accuracy of

the credit report information, disclose the inaccurate terrorist list match upon request, and include a notice of their rights under FCRA.

The class-action was filed on behalf of a class of 8,185 people all suffering from TransUnion’s matching practices. However, only 1,853 of the class, including Ramirez, had their false reports containing OFAC alerts provided to the third-party companies.

- Decision and Analysis: A Privacy Law Perspective

The Supreme Court held that members of the class-action lawsuit whose credit files were provided to third-party businesses suffered concrete harm from TransUnion’s actions. However, those whose files were not transferred lacked standing to sue under Article III. In our earlier article, we have discussed important procedural and policy issues and considerations related to this case. In the meantime, this case also has significant privacy implications because the Supreme Court significantly shaped the enforcement landscape for many privacy laws.

Specifically, from the privacy perspective, the Supreme Court restricted private rights of action in privacy actions by introducing a “concrete harm” for Article III standing to seek damages. According to the Supreme Court, “[c]entral to assessing concreteness is whether the asserted harm has a ‘close relationship’ to a harm traditionally recognized as providing a basis for a lawsuit in American courts.” TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 141 S. Ct. 2190, 210 L. Ed. 2d 568, 2200 (2021). In other words, a mere statutory violation does not give a plaintiff a cause of action against a defendant.

Taking into account the essence of many privacy violations and the notion of privacy harms2, determining what constitutes concrete harm exactly can be very challenging. In particular, as mentioned in the dissenting opinion of Justice Thomas, “even setting aside everything already mentioned— the Constitution’s text, history, precedent, financial harm, libel, the risk of publication, and actual disclosure to a third party—one need only tap into common sense to know that receiving a letter identifying you as a potential drug trafficker or terrorist is harmful.” TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 141 S. Ct. 2190, 210 L. Ed. 2d 568, 2223 (2021).

In this respect, the Supreme Court’s decision is highly criticized by leading privacy scholars as “undermining the effectiveness of many privacy laws” and being “wrong and troubling on many levels.” Id. According to Keats Citron & Daniel J. Solove, “the Court’s test for recognizing concrete injuries is severely flawed. The Court’s application of its test is also marred by an inadequate understanding of privacy harms”. Id.

These conclusions are based on the detailed analysis of the notion of “privacy harm” in the broad sense (including “emotional distress harm” and “data quality harm”). Indeed, it seems reasonable to argue that “a credit report with inaccurate information like denoting someone as a terrorist as in TransUnion poses a significant risk of economic and reputational harm” and “[i]t can be hard for individuals to find out about errors, and when they do, third parties will ignore requests to correct them without the real risk of litigation costs.”. Id.

However, despite the risk of future harm was not recognized as sufficiently concrete to satisfy Article III standing, the Supreme Court recognized that “a person exposed to a risk of future harm may pursue forward-looking, injunctive relief to prevent the harm from occurring, at least so long as the risk of harm is sufficiently imminent and substantial.”. TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 141 S. Ct. 2190, 210 L. Ed. 2d 568, 2210 (2021). Specifically, the Supreme Court clarified that when it is impossible to prove a “concrete harm,” there is still an opportunity to enforce statutory rights through the injunctive relief. In practice, this means that those whose credit reports contain inaccurate information could request TransUnion to amend this information, prohibit it from transferring with third parties, or undertake other measures aimed to prevent the harm from occurring.

Thus, from a privacy perspective, it provides guidance for courts and parties on how to assess intangible harms. In the meantime, the TransUnion case imposes significant limitations on the enforcement of privacy violations and, as mentioned in Thome v. Sayer L. Grp., P.C., “questions remain about how to implement TransUnion’s guidance.”. Thome v. Sayer L. Grp., P.C., No. 20-CV-3058-CJW-KEM, 2021 WL 4690829, 7 (N.D. Iowa Oct. 7, 2021).

- Post-TransUnion Case Law

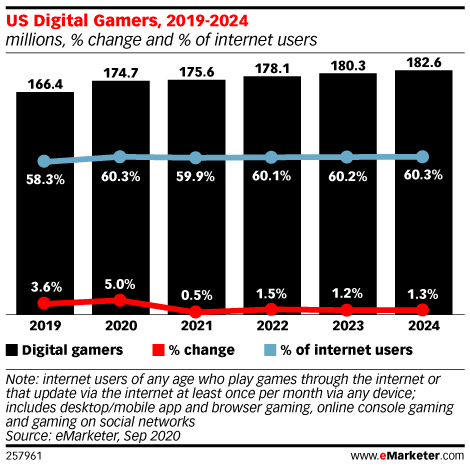

Interestingly, since the decision was delivered on June 25, 2021, courts actively applied and analyzed the TransUnion decision. As for February 2022, there are more than 300 decisions that, in their reasoning, referred to the TransUnion case4.

These cases include both those directly related to privacy violations, including privacy of communications as part of the debt collection litigation under FDCPA6 as well as a wide range of other class actions including antitrust, labor, First Amendment rights and specific state law statutes.

Despite the TransUnion decision only addressed federal court standing under Article III, courts tend to use TransUnion guidance in actions arising under state law.

For instance, it seems insightful to analyze the recent case considered in the Court of Appeals of the Second Circuit – Maddox v. Bank of New York Mellon Trust Company, N.A. Maddox v. Bank of New York Mellon Trust Co., No. 19-1774 (2d Cir. 2021)10. In this case, mortgagors (the “Maddoxes”) brought an action against the mortgagee, alleging that mortgagee’s failure to timely record mortgagors’ satisfaction of mortgage. The district court stated that mortgagors had Article III standing to seek statutory damages from the Bank for its violation of New York’s mortgage-satisfaction-recording statutes (the “statutes”).

The District Court denied the Maddoxes’ motion for judgment on the pleadings. Mortgagors filed an interlocutory appeal claiming to have Article III standing to seek statutory damages. The appeal was certified.

However, on rehearing in light of the intervening authority of TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, which was held after the TransUnion decision, the Court of Appeals of the Second Circuit held that mortgagors did not satisfy a test of “concrete harm”, and thus, they lacked Article III standing to pursue claims for statutory penalties in federal court. As part of its analysis, the Court of Appeals of the Second Circuit noted the following:

“In sum, TransUnion established that in suits for damages plaintiffs cannot establish Article III standing by relying entirely on a statutory violation or risk of future harm: “No concrete harm; no standing.”

“Our original opinion observed that a statutory right is considered “substantive” if it protects against a harm that has a close relationship to a harm traditionally regarded as providing a basis for a lawsuit in American courts. The violation of a substantive right, the opinion explained, constitutes a concrete injury in fact sufficient to establish Article III standing without any additional showing. TransUnion clarified, however, that the type of harm that a statute protects against is of little (or no) import; what matters is “whether the alleged injury to the plaintiff has a ‘close relationship’ to a harm ‘traditionally’ recognized as providing a basis for a lawsuit in American courts.” 141 S. Ct. at 2204 (emphasis added) (quoting Spokeo, 578 U.S. at 341, 136 S.Ct. 1540). In other words, plaintiffs must show that the statutory violation caused them a concrete harm, regardless of whether the statutory rights violated were substantive or procedural.”. Id.

As for the privacy-related post-TransUnion cases, the illustrative example is the recent case Bohnak v. Marsh & McLennan Cos., Inc. Bohnak v. Marsh & McLennan Cos., 2022 WL 158537 (S.D.N.Y. 2022).

In this case, plaintiffs (Bohnak and Smith) brought a nationwide class action complaint against defendants (specifically, companies Marsh & McLennan Companies, Inc. and Marsh & McLennan Agency, LLC) for alleged injuries arising from a data breach compromising plaintiffs’ personally-identifiable information in defendants’ possession. Plaintiffs bring state-law claims for: (1) negligence, (2) breach of implied contract, and, (3) breach of confidence.

In its analysis, the United States District Court (S.D. New York) made several references to the TransUnion case. In particular, the court noticed the following:

“Although TransUnion foreclosed Plaintiffs’ reliance on the mere future risk of harm, it did not foreclose Plaintiffs’ second theory. Plaintiffs may have Article III standing, so long as they plausibly allege that the exposure to identity theft itself “causes a separate concrete harm.” Bohnak, 2022 WL at 5. I hold that they do. Certain types of intangible harms have long been judicially cognizable, and are therefore, concrete. These include reputational harm and privacy-related harms that form the basis for the common-law torts of defamation, public disclosure of private information (“PDPF”), and intrusion upon seclusion.”

“In light of the TransUnion Court’s admonition that common-law analogs need not provide “an exact duplicate,” as well as its explicit reference to PDPF as an example of traditionally judicially cognizable intangible harm, I find the fit sufficiently close. Accordingly, I hold that Plaintiffs have alleged an intangible concrete injury, analogous to that associated with the common-law tort of public disclosure of private information, and therefore have Article III standing.”. Bohnak, 2022 WL at 5.

Thus, the Court applied the TransUnion decision to determine the criteria for public disclosure of private information. Interestingly, despite the claim was overall dismissed for failure to state a claim11, the Complaint managed to satisfy the requirements of Article III, as prescribed by the TransUnion decision, and shed light on the application of the TransUnion “concrete harm” test in privacy-related cases considered in the Second Circuit.

- Trends and Conclusions

Overall, TransUnion v. Ramirez is a landmark case that has debatable, but definitely strong influence on Article III standing regarding concrete harm, including enforcement in privacy-related cases. In particular, the TransUnion “concrete” harm test is adapted by courts of the Second Circuit.

In practice, this means that now plaintiffs, including those who are willing to enforce their privacy rights in the Second Circuit and, specifically, recover damages, should take into account the necessity to show the evidence of “concrete” harm as defined by the Supreme Court in TransUnion v. Ramirez. Otherwise, plaintiffs may consider pursuing an alternative course of action (e.g., injunctive relief).

1 TransUnion LLC v. Ramirez, 141 S. Ct. 2190, 210 L. Ed. 2d 568 (2021); Statutory Violations Not Enough to Give Rise to a Cause of Action for Class Actions says U.S. Supreme Court.

2 Citron, Danielle Keats and Solove, Daniel J., Privacy Harms (February 9, 2021). GWU Legal Studies Research Paper No. 2021-11, GWU Law School Public Law Research Paper No. 2021-11, Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3782222 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3782222.

3 Solove, Daniel J. and Citron, Danielle Keats, Standing and Privacy Harms: A Critique of TransUnion v. Ramirez (July 28, 2021). 101 Boston University Law Review Online 62 (2021), Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3895191.

4 Specifically, based on the Westlaw search, as for February 01, 2022, there are 312 cases where courts referred to TransUnion v. Ramirez.

5 See e.g., In re American Medical Collection Agency, Inc. Customer Data Security Breach Litigation, Slip Copy (D.N.J., 2021), Wadsworth v. Kross, Lieberman & Stone, Inc., 12 F.4th 665 (7th Cir. 2021), 12 F.4th 665, 668–69 (7th Cir. 2021); JOSE AVINA, Plaintiff, v. RADIUS GLOBAL SOLUTIONS, LLC, Defendant., No. 21 CV 295, 2021 WL 6752293 (N.D. Ill. Nov. 4, 2021); Bohnak v. Marsh & McLennan Cos., Inc., No. 21 CIV. 6096 (AKH), 2022 WL 158537 (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 17, 2022).

6 In re FDCPA Mailing Vendor Cases, No. CV 21-2312, 2021 WL 3160794, at *1 (E.D.N.Y. July 23, 2021), Lupia v. Medicredit, Inc., 8 F.4th 1184 (10th Cir. 2021), Kola v. Forster & Garbus LLP, No. 19-CV-10496 (CS), 2021 WL 4135153 (S.D.N.Y. Sept. 10, 2021); Sputz v. Alltran Fin., LP, No. 21-CV-4663 (CS), 2021 WL 5772033 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 5, 2021).

7 See e.g., In re EpiPen (Epinephrine Injection, USP) Marketing, Sales Practices and Antitrust Litigation, Slip Copy (D.Kan., 2021)

8 Ellsworth v. Schneider National Carriers, Inc., Slip Copy (C.D.Cal., 2021); Rosario v. Icon Burger Acquisition LLC, No. 21-CV-4313(JS)(ST), 2022 WL 198503 (E.D.N.Y. Jan. 21, 2022).

9 CARLOS VICTORINO & ADAM TAVITIAN, individually, & on behalf of other members of the general public similarly situated, Plaintiffs, v. FCA US LLC, a Delaware limited liability company, Defendant., No. 16CV1617-GPC(JLB), 2021 WL 4124245, at *4–5 (S.D. Cal. Sept. 9, 2021); Ass’n of Am. Physicians & Surgeons v. United States Food & Drug Admin., 13 F.4th 531 (6th Cir. 2021)

10 Maddox v. Bank of New York Mellon Tr. Co., N.A., 19 F.4th 58, 59 (2d Cir. 2021).

11 As mentioned by the Court, “it [the Complaint] ultimately falls short in establishing that Plaintiffs have suffered legally cognizable injury to support their substantive claims.”